The best Indian food is available at your Indian friend’s home

It's time to stop hunting for the "best Indian restaurant"

When people discover I write about Indian food and sell ready-to-cook curry pastes, I get one of two reactions:

They guiltily admit they always order/cook butter chicken

They ask me about my favourite Indian restaurant

I think it’s time I admit this to you. I enjoy butter chicken as much as you do.

It’s creamy, smoky and comforting when you’re having the real deal. My war is with the radioactive orange butter chicken that tastes like ketchup and cream with bland chicken floating around.

But it’s the second point I want to chat about. Because, I have no favourite restaurant.

I only go eat at an Indian restaurant once a year to get my fill of naan. The rest of the time, I believe the best Indian food is eaten at home.

Food in a restaurant is heavy

The first time I ate butter chicken in New Zealand, I ate it because I was homesick. The aroma of garlic and chilli wafting in the air near the Shamiana stall in the food court reminded me of home. I got the $9 butter chicken rice and naan combo and dug in.

It tasted familiar but also strange.

Later as I tried to get the orange stains off my fingers in the bathroom, I burped uncomfortably. I had enjoyed the food while I ate it, but now I felt sick. The butter chicken settled uncomfortably heavy in my stomach. I learned to expect this feeling every time after many $9 (and some $29) bowls of butter chicken, tikka masala, and mango chicken.

Curiously, I never feel like this when I eat Indian food at home or a family/friend’s house.

My friends cook for me as they would for their family. With love. And patience. This means that while the Aloo Gobi, Saagwala, Dal Makhani and Methi (Fenugreek) Paratha is lip-smacking, it’s not loaded with cream, salt or sugar, a shortcut almost all restaurants use, Indian or otherwise, to get you to order more.

At home, I feel satisfied and full at the end of the meal. Not like there's a 5kg rock resting at the bottom of my stomach that I need to burp out.

At home, every dish tastes different

When my family goes to an Indian restaurant, we (mostly me, as I’m always dumped with the ordering) take pains to each order a different thing so we get to “have some variety”.

But when it arrives at the table, almost all of it is reddish brown, thick layer of ghee or oil floating on top, with a similar heavy butter aroma lingering in the air. You’ll see this at the food court too where each gravy is a different hue ranging from radioactive orange to a creepily pink maroon (normally the Vindaloo).

As I take a bit of each dish onto my plate and start to scoop it up with my naan, the tastes all blend together and I feel like I’m having one homogenous dish. Kind of like how all McDonalds burgers taste the same.

I used to think it was my imagination. Until I cooked inside a restaurant for a popup and learned that restaurants operate on a “base sauce” principle. A spicy onion-tomato base. A creamier tomato sauce. It’s all pre-prepared, and then the chicken, goat, or vegetables are added in based on what you order.

For obvious reasons, that’s not how food is cooked at home.

The Cabbage Potato Shaak I eat at my friend’s home tastes of cabbage. Even though I eat Chicken Biryani and Salli Chicken on the same plate, the biryani chicken tastes smoky, while Salli Chicken is sweet and sour.

And even though the Dahi Kadhi and Keralan Meen Moilee are a light yellow and described as “simple”, the former has a sour tang from the yoghurt while the taste of ginger and coconut oil lingers on my tongue as I take the final bite of my Moilee.

Almost all restaurants serve the same 30 dishes

I’m currently testing out an Indian food walk in Sandringham, the Auckland suburb known for its Indian eateries. We go to seven different restaurants, eating a single dish everywhere.

One of my guests pointed out something strange to me. Despite their ‘specialities’, they all served the same dishes. The street food restaurant served tikka masala. The Biryani place had a Goan Vindaloo. And a joint focused on Mumbai food still served Butter Chicken.

While I understand it’s important for a commercial venture to serve what sells, what happens is that the uninitiated stick to what’s familiar, missing out on the delicacies. It’s like me going to Italy and missing out on the wholesome Puttanesca and lightly crunchy Fritto Misto because I got busy eating pizza!

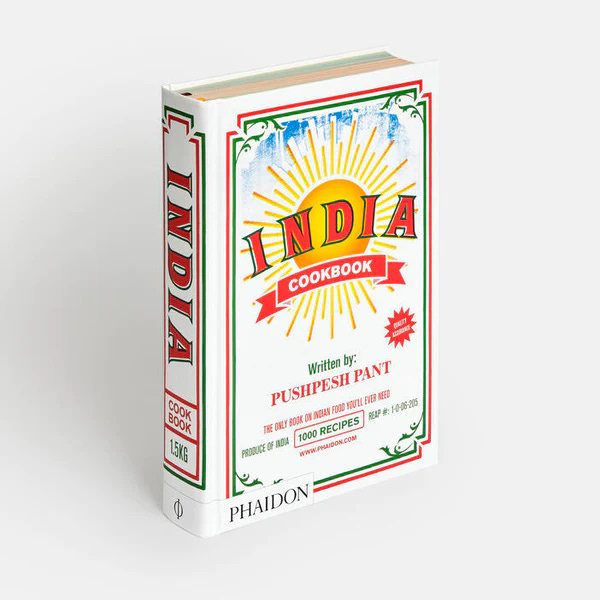

In India, the cuisine completely changes every 100km. Pushpesh Pant’s seminal cookbook, India, which contains 1000 recipes gives you a clue to the diversity you can expect. So when you go to someone’s home, you’re in for surprising experiences depending on what part of India your friend is from.

Both the Parsi Salli Boti and the Bengali Kosha Mangsho can be literally translated to “mutton curry”. But the former will be sweet and sour and served with crunchy potato sticks, while the latter has a charred complex flavour from slow-cooking goat meat in a wok for hours.

Gujarati, Rajasthani, Sindhi, Parsi, Bengali. Each community has hundreds of curries you can discover and indulge in at your friend’s home.

So rather than scouring Facebook groups for restaurant recommendations, spend that energy befriending your local Indian and try to score an invite to their home.

It won’t be hard. There are more than one billion of us.

Indian food is a vibrant tapestry of flavors and spices, featuring diverse regional cuisines that range from the fiery curries of the south to the aromatic biryanis of the north. It showcases a symphony of tastes, textures, and colors, reflecting the country's rich culinary heritage.

Well researched and fascinating! Indian food takes so much time and love and patience. I liked how you parsed out the differences in the food based on region. Thank you!